“To accept that pain is inherent and to live our lives from this understanding is to create the causes and conditions for happiness.” — Suzuki Roshi

“To accept that pain is inherent and to live our lives from this understanding is to create the causes and conditions for happiness.” — Suzuki Roshi

The thesis here is: beware of the assumption that (with a little right- headedness) we can and should minimize the impact of adversity in our lives; or that inner strength, as well as compassion for ourselves and others should somehow be easily within our grasp. Rather,it will be argued, we might be better off embracing misery, pessimism and minimal ambitions for our inner life. To wit:

expectations of happiness –> misery

expectations of misery –> happiness

The modern day assumption (largely psychological in nature) that- if only we could eliminate the toxic effects in our life- happiness would be forthcoming, has regrettable, if paradoxical consequences. The effort to either vanquish or avoid inner demons and other insults, we will argue, empowers the demons and diminishes us. We suffer more in the name of happiness than derive pleasure from it.

But first a caveat: the arguments offered below do not apply to the suffering involved in clinically significant disorders, such as the disorders that are the focus of this website. Add to those, the wider range of disorders listed in DSM – 5. These disorders are destructive and deserve to be counteracted. Fortunately, there are effective treatments for many of them.

So, what is the arena of suffering in which these arguments are offered? To say simply that suffering is inherent to existence is too abstract. Steven Hayes, the founder of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, makes it more concrete when he says, “This kind of suffering is the elephant in the room no one is acknowledging; namely, it is hard to have compassion for ourselves and others. It is hard to be a human being.”

The late David Foster Wallace, fiction writer and essayist, brings it alive when he offers the following vignette:

The next person you’re in light conversation with, you stop suddenly in the middle of conversation and look at the person closely and say, “What’s wrong?” You say it in a concerned way. He’ll say, “What do you mean?” You say, “Something is wrong. I can tell. What is it?” And he’ll look stunned and say, “How did you know?” He doesn’t know that everybody’s always going around all the time with something wrong and believing they’re exerting great willpower and control to keep it hidden from other people, for whom they think nothing’s ever wrong. (From the Pale King)

That kind of suffering.

What do we mean by ‘set your baseline at suffering’? We mean: consider cultivating a framework where happiness, equanimity, and loving human connection are not our birthright. Nor the norm. Nor can they be perfected. While it may be desirable to behave in a manner to pursue them, it is also desirable to recognize that such a mission cannot be accomplished in a lifetime.

The norm is more like the suffering of Adam and Eve after the loss of innocence. The norm is fallibility and struggle. However, we do want to push back on the severe shame and punishment that were inflicted on Adam and Eve after their fall from grace. But the main push back-paradoxically- is to increase the arena of acceptable suffering.

We also mean: try to approach rather than avoid suffering. Be receptive to suffering by taking the following steps: acknowledge it, accept it, be open to its meaning (including the possibility that, although it appears as an ugly root, it could turn into a flower). Don’t strive to feel good. Do strive to feel good.

Advantages of Embracing Suffering

- It enhances resilience, resilience considered by many to be the cardinal trait related to long-term happiness.

We must embrace pain and burn it as a fuel for our journey.

– Kensi MiyazawaAdversity has the same effect on a man that severe training has on a pugilist:

it reduces him to his fighting weight. – Josh Billings - It is folly to try to avoid suffering.

When suffering knocks at your door and you say there is no seat for him, he tells you not to worry because he has brought his own stool.

– Chinua AchebeThe Truth that many persons never understand until it is too late is that the more you try to avoid suffering, the more you suffer because smaller and more insignificant things begin to torture you in proportion to your fear of being hurt. – Thomas Merton

To regard states of distress in general as an objection, as something that must be also abolished, is the supreme idiocy….almost as stupid as the will to abolish weather.

– Frederick Nietzsch - Not facing suffering actually increases it’s power (and not in a good way).Once we take the stance that we cannot stand to face some adversity in our life or some painful, tangled internal state, we ensure that struggle is placed at the center of our concerns. Then, to make matters worse, instead of contending directly with the difficulty we get hung up on the having to contend. Steven Hayes, founder of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, makes the distinction between clean pain and dirty pain. Clean pain is the original discomfort we feel in response to a real life problem. Dirty pain is the pain we get when we needlessly struggle to control, eliminate, or avoid clean pain. Thus, his guideline: Contend with clean pain. Avoid dirty pain.

- Facing hard truths about oneself allows true acceptance .One of the central goals in therapy is to help the client make room for those thoughts and feelings that the client finds most frightening and shameful. At the heart of much distress is self-mistrust — the notion that our innermost thoughts, feelings and longings are dangerous or bad. These so-called inner demons must then be disavowed. But this can lead to “holes” in the personality (e.g. I must not be angry, or competitive,or sexual, etc) and a loss of authenticity. Therapy, when it works, helps people re-appropriate those disavowed feelings so they can either be accepted and integrated into a more authentic self or explored so a genuine transformation is possible.

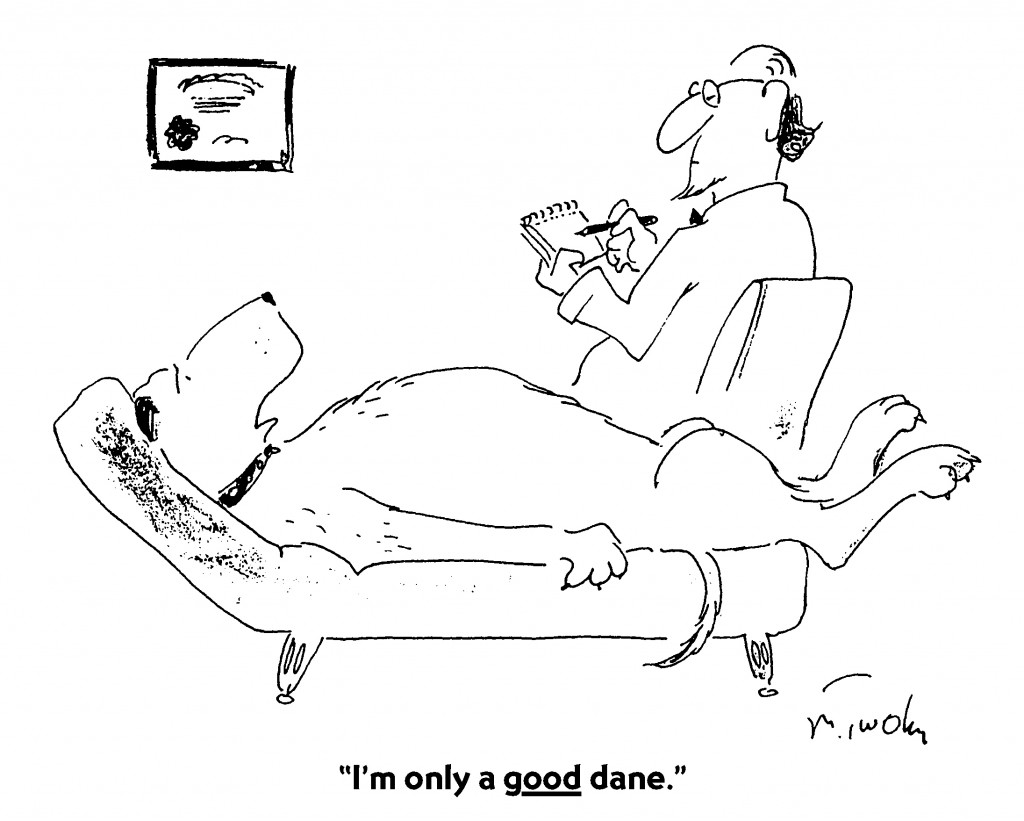

- Break through the superficiality of “I’m OK/You’re OK”. To do this requires an expanded view of ourselves as fallible — wretched, jealous, bored, pitiful, petty, and so on. It also requires putting aside ambitions to perfect our human nature, and to entertain putting aside the narrative that self-improvement can somehow take us to a place where we are simply good and strong. The task is how to contend with our flawed nature rather than perfect it. Instead of the flaccid acceptance of the “I’m OK/You’re OK” variety, it’s the more tragic perspective of “I’m not OK/You’re not OK and we’re never going to be OK, but it’s OK”. This more tragic view of human nature and life opens the door to…..

- Consolation.When we accept our fallibilities we receive the consolation we are not alone.

“Everybody is identical in their secret belief that way deep down they are different (and not in a good way) from everybody else”.

– David Foster WallaceRather than uniquely screwed-up, we are part of the pitiful mass where misery is the norm, not a personal failure. French philosopher, Blaise Pascal, in his book Pensees, notes that we are more often thrown into despair by hope than pessimism. Modern day secular hope is rushing at us from all directions in the form of untapped potential, inner beauty and be all you can be. It is a relief to read an author that pounds hope into dust. Who tells us we are not alone and may not need to feel shame about sides of ourselves that we perceive to be possessive, insecure, apathetic, narcissistic or even perverse.

- Adversity may contain the seedlings of deeper fulfillment. Andrew Solomon, a student of adversity,in his elegant book, Far From The Tree, interviewed many victims of extreme adversity and was struck by how such victims felt indebted to their enemies and/or shattered experiences. They felt that way because they were able to forge meaning out of their traumatic experience. Solomon criticizes the concept of “finding” meaning. Deeper meaning and fulfillment are forged, not found. As a general rule, we don’t forge meaning out of the ordinary, but from hardship. It is not our delights that define us, but our struggles. Adversity is not a gift. But in the way we respond to it, adversity may become precious. Our greatest joys often lie awkwardly close to our greatest griefs.Solomon relates one interview with the mother of a child with down’s Syndrome who was 23 years old at the time of the interview. Solomon asked her if she wished her son had not had Down’s Syndrome. She replied, “For David, yes. His life would have been easier and he would have had better choices. But speaking just for myself? I am a kinder person than I ever would have imagined 23 years ago. For myself, I wouldn’t give it up for anything in the world.”

- Emotional pain is a necessary and valuable signal that, if responded to wisely, can lead to growth.Michel de Montaigne, a 16th century French philosopher, considered the world’s first memoirist, developed a generous and redemptive philosophy largely by acknowledging his own frailties and all- too- human vices. In Essays, using himself as a teaching model, he encourages the cultivation of adversity:

We must learn to suffer whatever we cannot avoid. Our life is composed, like the harmony of the world, of discords as well as of different tones, sweet and harsh sharp and flat, soft and loud. If a musician liked only some of them, what could he sing? He has got to know how to use all of them and blend them together. So too must we with good and ill, which are of one substance with our life.

Frederick Nietzsche agrees. He argues that difficult emotions should be seen as roots — albeit ugly and knotted — that need to be nourished. Humanity is compromised if they are viewed only as weeds to be cut out of life. Thus:

The emotions of hatred, envy, covetousness and lust of domination are life-conditioning emotions…..which must fundamentally and essentially be present in the total economy of life.

To exorcise difficult and painful feelings is to cut off the possibility of growth.

- Avoid getting old at the beginning of life. There is a philosophical divide on how to live the good life. On one side (which this blog post challenges) are Schopenhauer (“the prudent man strives for freedom from pain”) and the Utilitarians, exemplified by John Stuart Mill:

Actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain and the privation of pleasure.

On the other side are the Existentialists who favor fulfillment over happiness. They observe that, while we cannot spontaneously engineer the ingredients of fulfillment, the most fulfilling human projects cannot avoid suffering. Becoming a parent, climbing Mt. Everest (and all it’s metaphorical equivalents), producing an artistic, scientific or technical breakthrough, typically requires toil, torment and tolerance of threat. A focus on avoiding pain runs the risk of producing excessive caution, foreclosing deeper fulfillment, and making one old at the beginning of life.