HOW TO BE BETTER: THE POWER OF HABIT

The purpose of this module is to help you create desired habits. The module (shamelessly) borrows the key points made in two recent books on habit change: Better Than Before by Gretchen Rubin and The Power of Habit by Charles Duhigg. Each book is a lucid, user-friendly, New York Times bestseller that incorporates recent research on habit control

If you have the time and interest, you are certainly encouraged to read them.

Think of this module as a crib sheet that outlines the key points from their efforts. The format chosen is to answer the Who, What, Why, Which, When and (most importantly) How of habit change.

First….

What is a Habit?

This is an important question. A term like habit can mean different things to different people. To study habit formation scientifically, we need an agreed upon definition.

A useful definition? A habit is a behavioral routine, related to meaningful goal or value, that occurs in a particular context and has become automatic.

Automatic turns out to be a key feature of habits. Automatic means that the behavioral routine (e.g. stopping by the office gym twice a week before lunch; driving your daughter to soccer practice each week) goes on after we stop thinking about it.

Gretchen Rubin characterizes this state as “deciding not to decide.” She says:

This is the key to decision making — or, more accurately, the lack of

decision making. A habit requires no decision from me because I’ve

already decided. Am I going to brush my teeth when I wake up? Am I

going to take this pill? I decide then I don’t decide. I act mindfully, then

mindlessly. I shouldn’t worry about making healthy choices. I should

make one healthy choice and then stop choosing. The freedom from

decision making is crucial, because when I have to decide — which often

involves resisting temptation or postponing gratification — I tax my

self control.

Recent research on how habits work at a neurological level has enabled us to define habit in a way that can be measured and therefore investigated in a more robust and precise manner. Charles Duhigg in reviewing studies that used neuro-imaging and other advanced technologies, reinforces this point. Once a behavior becomes automatic, it is regulated by a different part of the brain that is associated with less effort, less depletion of resources (what habit experts call ‘self-central reserves’).

We have advanced from preaching about habit change, to the application of behavior modification strategies to effect it, to the discovery of a physical marker to measure it.

Why Change?

If you are taking the time to read this module, you already know the answer: you are investing effort and intellectual reserves to learn about habit change because there is a new habit you want to create or some undesirable pattern you want to change. Meeting your goals and living your days more in line with your values is the most important reason to change.

In addition, relying on the findings of leading researchers and thinkers on habit change and self-discipline, we can point to other benefits, such as:

- Improved health

- Longer life

- Coping more effectively with stress

- Increased happiness

- Enhanced self-esteem

- Greater respect from others

- Better professional success

- Improved focus

- Greater confidence

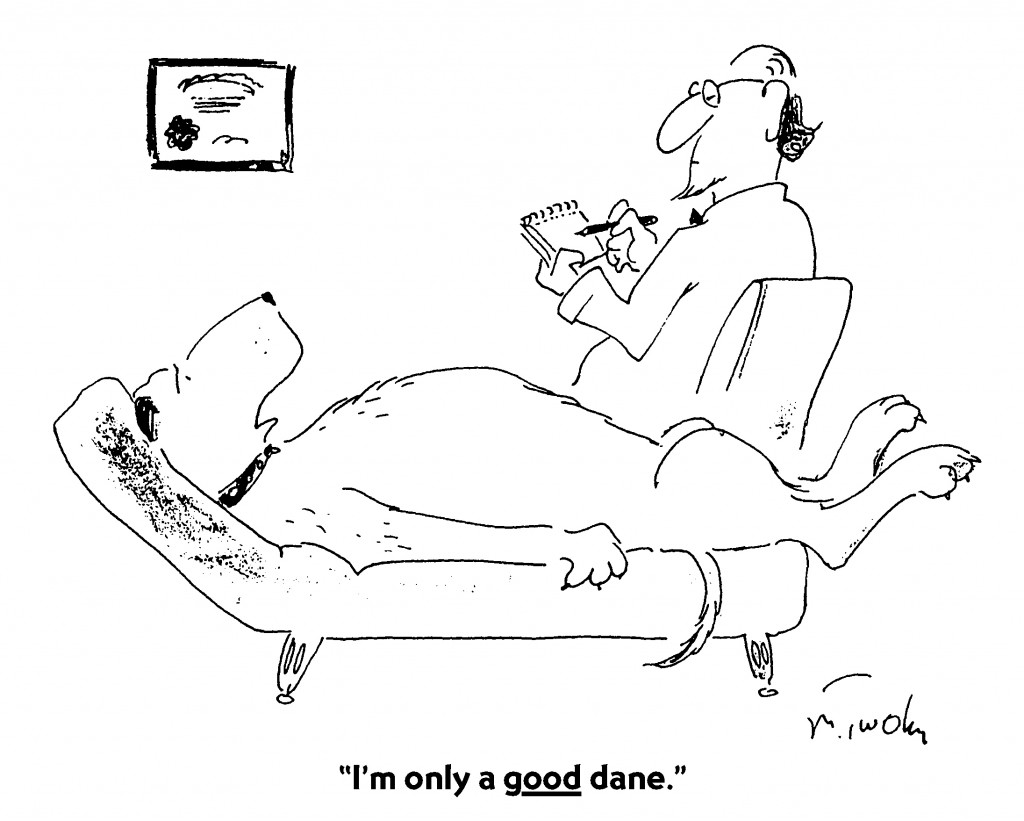

Perhaps the key advantage of creating good habits is revealed in the above noted, research-driven definition of habit: habits conserve energy.

After we decide what we want to change; (e.g. lose weight, spend more time with family) and once we figure out the behavioral routine to help get us there; and once that routine becomes automatic; then we can bank self-control reserves. With those reserves, we can pursue other fulfilling endeavors and/or have a less harried, more peaceful state of mind.

Who is Changing?

Who will create a new habit? You, of course. But who are you? With this question, we are asking? Are there important qualities to know about yourself to help create a new habit?” The answer is yes.

Gretchen Rubin has identified four tendencies or personality types that significantly inform how to establish a new habit. These tendencies are psychological dispositions of how we respond to expectations. Expectations can be inner (e.g. New Year’s Day Resolutions) or outer (e.g. work deadline). How do you respond to these two types of expectations? Depending on your answer you will fall into one of the four groups in the table below.

Upholders respond well to outer and inner expectations. Habit change is the easiest — although not necessarily easy — for this type.

Questioners respond well to inner expectations, but not to outer expectations. Questioners need to be clear with themselves that creating a new habit is worthwhile. They tend not to be swayed by rules or other’s expectations. Once a Questioner determines their own rationale for a habit, they are more likely to be successful.

Obligers do try to meet other’s expectations and are motivated by deadlines and rules. A core strategy for Obligers is to build in some kind of external accountability for habit change, such as going to the gym with a friend or joining an exercise class or running group.

Rebels fight inner and outer expectations. Habit change, therefore, is difficult for Rebels ( Rubin estimates that Rebels make up 5% of the population ). One core strategy is to encourage Rebels to identify habits that line up with their chosen values. Another strategy is to encourage them to think through the advantages and disadvantages of developing a particular habit.

ln addition to highlighting this key trait of how one responds to expectations, Rubin provides a list of questions to identify other traits that can help one design a habit change strategy. To wit:

Am l a lark (morning person) or an owl (night person)?

If you are a lark, you wouldn’t want to plan the time of your new habit (e.g. exercising, studying) after dinner.

If you are an owl you probably don’t want to execute your new habit in the morning when you are not naturally energetic or productive.

lf you are not clearly a lark or an owl, you may want to work on your new habit in the morning. Research suggests we have more reserves of self-control earlier in the day. And you may want to nudge your lark tendency: research also suggests larks are a bit more happier and healthier than owls.

Am l a marathoner, sprinter or procrastinator?

A marathoner is someone who works in a deliberate, steady and slow manner. Marathoners accrue energy by seeing steady progress. Marathoners are not particularly motivated by deadlines.

Sprinters prefer quick bursts of energy. Sprinters do respond positively to the pressures of a deadline.

Marathoners and sprinters appreciate their style of pace and increase the likelihood of creating a new habit by working within that style. Thus, no need to change their style.

Procrastinators are not happy with their work style and need to change it (more on how later).

Am l an underbuyer or overbuyer?

An underbuyer hates to shop and buy. An overbuyer loves to shop and buy.

How does this relate to habit change? An underbuyer should be encouraged to spend (e.g. acquire good running shoes) to support a new habit. An overbuyer needs to realize that acquisitions (“once l get the right equipment l will get in shape”) are, at best, minor factors in habit change.

Am l a simplicity lover or an abundance lover?

Simplicity lovers are drawn to “less” e.g. a roomy closet, bare surfaces, less choices, less noise.

Abundance lovers are drawn to “more” e.g. a full closet, stocked shelves, more choices, more stuff.

Simplicity lovers work better in environments that are quiet and empty; abundance lovers generally prefer some bustle, and work spaces with rich visual detail.

Simplicity lovers are drawn to habits that involve simplification and elimination (e.g. saving money, reducing caloric contact); whereas abundance lovers are drawn to addition and variety (e.g. making more money, enriching their diet).

Am l a finisher or a starter?

Finishers are particularly satisfied when they finish a project. Starters are excited by starting a project. Thus if a finisher wanted to cultivate the habit of creative writing, she might want to have a daily marker of accomplishment such as completing two paragraphs: whereas a starter may want to reinforce her enthusiasm by exploring websites that offer writing tips.

Am l a familiarity lover or a novelty lover?

Familiarity lovers enjoy doing the same things e.g. vacationing at the same spot, eating the same foods. Habits become easier for such people when they become familiar.

Novelty lovers seek out new experiences. Such people may take to habits that enable them to take on new projects and challenges.

Am l promotion-focused or prevention-focused?

Am l focused on advancement and achievement; or avoiding losses and dangers?

A promotion-focused person may increase their exercise routine to look more attractive or become better at a sport; whereas a prevention-focused person might exercise more to prevent health difficulties or injuries.

Do l like to take big steps or small steps?

For some people, having audacious goals gets them motivated. For most people, however, taking small steps is more realistic. The key is to take some small step. Research suggests that taking even very small steps (e.g. one pushup, writing one sentence, set alarm to wake up two minutes earlier) is predictive of taking the next step and then the next step and so on.

Fostering the habit of habit builds an infrastructure in your brain that makes virtuous behavior more automatic. The result? More success in realizing your goals and the freeing up of self-control reserves to take on more challenging goals.

When To Start A Habit?

NOW

“Distance is nothing; it’s only the first step that is difficult.” Amelia Earhart.

For most people the first step is the hardest; alas, it is also the most important.

To help you take the first step, consider the following:

One of the more exhausting states of mind is to focus on the unfinished task, the put-off resolution. Starting shifts the mind gear from this enervated mode to a more energized, productive mode.

- “ The first step binds one to the second” (French proverb). Taking the first step – no matter how small – raises the chances of taking the next step.

- Reclaim the power of NOW. Tomorrow will always seem like a better time to start. But NOW is where life is lived, choices made, power asserted.

- Picture one of those old steam engine trains with large wheels. The train is revving up to start a journey. The boilermen are expending sweat and muscle, pouring coal into the furnace, to get the train moving slowly out of the station. For a moment you doubt whether the train has the energy to keep inching forward. But it does. And in a few minutes the train is barreling down the tracks, making headway, carried by it’s own momentum.

- You may be in the group of people that responds better to starting with a big, demanding step (e.g. “Today l will write the first chapter of that book.” “l will schedule a 90 minute session with a trainer to jump start my exercise routine.”). For you, the challenge of a big step is energizing rather than intimidating. Know yourself.

When To Stop a Habit?

Try never, never works

“ In the acquisition of a new habit, or the leaving of an old one, we must take care to launch ourselves with as strong and decided an effort as possible…Never suffer an exception to occur till the new habit is securely rooted in your life. Each lapse is like the letting fall of a ball of string which one is carefully winding up; a single slip undoes more than than a great many times will wind again.”

– William James

* The idea here is not to simply get rid of bad habits, but to replace them with habits that are in line with your values, habits that you honestly want to incorporate in your life (e.g. eat healthy, exercise regularly, read carefully).

* Beware of a finish line, a once-and-for-all goal (e.g. lose 30 lbs). A finish line is often a formula for relapse since it creates a vacuum that will eventually be filled by the old pattern.

* It is harder to restart a habit than continue one.

Which Habits to Cultivate?

We now know there are some habits that are “better” than others. These better habits have a synergistic quality. Thus, when these habits take root, they trigger other desirable habits. Therefore, there is a ‘get two (or even three) for one’ quality to these habits.

Gretchen Rubin refers to these habits as foundational: Charles Duhigg labels them as keystone habits.

In addition to making other habits easier to acquire, these habits:

- Increase sense of well-being

- Increase productivity

- Increase willpower

There is a good deal of consensus on which habits are foundational. Most experts emphasize the four habits listed below with their scientifically-proven benefits.

Sleep

- Energy level not depleted

- Reduce stress/risk of depression

- Improve attention and memory

- Live longer/maintain a healthy weight • Increase energy level

- Improve mood/feeling of calm

- Improve executive functioning

- Improve health outcomes/weight maintenance

- Increases productivity

- Controls weight

- Boosts mood

- Improves health

- Saves time/boosts energy

- Greater sense of self-control

- Facilitates productivity

Exercise Regularly

Eat and Drink Well

Decluttering

Keystone habits — habits that cause other good habits to fall in line — are not necessarily more difficult to acquire. Indeed, a key feature of keystone habits is that they provide a sense of small, but consistent victories.

A good example of a keystone habit is keeping a food journal, in which you keep a record of everything you ate or drank during the week, the time and place, and the emotion you were having at the time. Every record-keeping act is a small, but consistent success.

It also establishes a routine that can trigger desirable changes. For example, you may notice you eat a lot while watching a football game, but are barely aware of enjoying the food. Or you might notice you overeat when feeling anxious. These observations can lead to changes in your eating